Hillary Reder is an Assistant Curator of Modern Art at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (TAMA). She came to Tel Aviv after living in New York for several years, where she worked at the Museum of Modern Art. Over the last year, she was involved in bringing a portrait by iconic New York painter Alice Neel into TAMA’s collection. Relieved and happy that a fellow New Yorker joined her in Tel Aviv, she writes about their parallel transatlantic journey.

Text editing: Einat Adi

Visual resources and copy rights: Yaffa Goldfinger

I moved from New York to Tel Aviv in September 2020, and joined the Modern Art Department at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art several months later. There is a lot I miss: four distinct seasons, understanding what people are saying, the Subway, and of course (and this is really not a complaint about Tel Aviv’s scene, it’s just that New York is New York…), I miss seeing all the exhibitions coming and going.

One recent show I read about from my new vantage point as a non-New Yorker was Alice Neel: People Come First, the 2021–22 retrospective organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Alice Neel, relatively unknown in Israel, was an American figurative painter active in New York from the 1920s to her death in 1984.

I first encountered Neel’s work in depth at an important show at David Zwirner Gallery in 2017. I also learned that in the last years of her life, she lived just two blocks from my Upper West Side apartment, and I often thought of her working as I walked by her building, inviting in a stream of sitters, painting one portrait after another.

It was a very unexpected and welcome surprise to hear, soon after I began working at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, that we had been offered an early Alice Neel portrait by collectors from Long Island, Edith and Alvin Orlian. The painting is a penetrating 1940 portrait of Tony Mattei, a man depicted with something of a resigned expression, his lips held tightly together and his left eyebrow rising quizzically, counterbalanced by his lifted right shoulder. While his frontal, upright pose is somewhat formal, his right leg is hiked up at a surprising angle—lending his posture a spontaneous, casual quality. The leg appears weightless, almost recalling draped fabric more than a solid limb.

Seated against a sienna background, Mattei is wearing a crumpled, velvety brown suit, with a matte crimson neck tie. His skin is a medley of yellowish browns and tans and some orange highlights. These earthy tones project a kind of muted autumnal harmony, pierced by the man’s extraordinary aquamarine eyes. A shock of the same oceanic color appears on the chair’s backrest. Like many of Neel’s paintings, a lack of a perfected finish imbues the work with a life-like quality. There is a vivid, slightly jarring aspect in her work, conjured by Neel own’s wry observation that, “Maybe these portraits jump out at you too much. People like things that conform.”

While nothing of his demeanor or clothing strongly suggests Mattei’s profession—in the cast of characters that animate the canvases of Alice Neel he may have been a left-wing politician, a neighbor, or a lover—he was a fellow painter. Perhaps Neel’s rendering of his large, capable hands, held in a dynamic posture of self-possession, hints at this. Like Neel, Mattei was a member of WPA Federal Art Project, a Depression-era New Deal program that guaranteed artists a monthly income, as well as a supply of 24×30-inch canvases, such as the one used here. While not much more is known about their relationship, they shared a commitment to representational art at a time in New York when abstraction unquestionably dominated. An example of Mattei’s work can be found here.

When Neel made this work, she was living in Spanish Harlem (where she lived for twenty years before moving to the Upper West Side)—a neighborhood made up of Dominican and Puerto Rican immigrants—an unusual choice for a white artist at a time when the epicenter of the art world was downtown. Neel was tired of what she called the “honky tonk” atmosphere of Greenwich Village, and sought a more authentic environment, in her words, one with “more truth.” After early efforts in cityscapes and narrative-driven scenes, she turned her focus exclusively towards portraiture in Harlem. She invited neighbors, friends, artist acquaintances and others to her apartment so she could paint their portraits. She would have painted Mattei in this same studio, entertaining him with witty conversation over the course of the sittings—a technique of Neel’s that disarmed her models, allowing their authentic body language and facial expressions to emerge.

To be both a woman and a realist painter in the macho mid-century New York art world dominated by abstract expressionists and minimalists was not exactly an advantage for Neel. After working in near-obscurity from the 1920s to the 1950s, she gained some renown by the end of her life, becoming something of a cult figure. She painted portraits of artists such as Andy Warhol and Faith Ringgold, and art historians such as Linda Nochlin and Meyer Schapiro. But it was not until the last fifteen years, with the recent run of major exhibitions, that her status as one of the most important painters of the twentieth century has been widely recognized.

It is a privilege to present Alice Neel’s art at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art—perhaps the only work of hers in an Israeli collection. The gift of the painting is all the more significant because the Modern Art Department relies on the generosity of donors to expand the collection. Donations sometimes develop from relationships and conversations over the course of many years. Others occur suddenly, with the museum staff hardly able to believe their good fortune. The Neel donation was one such case: after their son-in-law Mitchell Presser, a longtime supporter of the Museum, made the introduction, the Orlians offered to make their painting a permanent gift. We enthusiastically accepted, and six months later, the painting arrived in Tel Aviv.

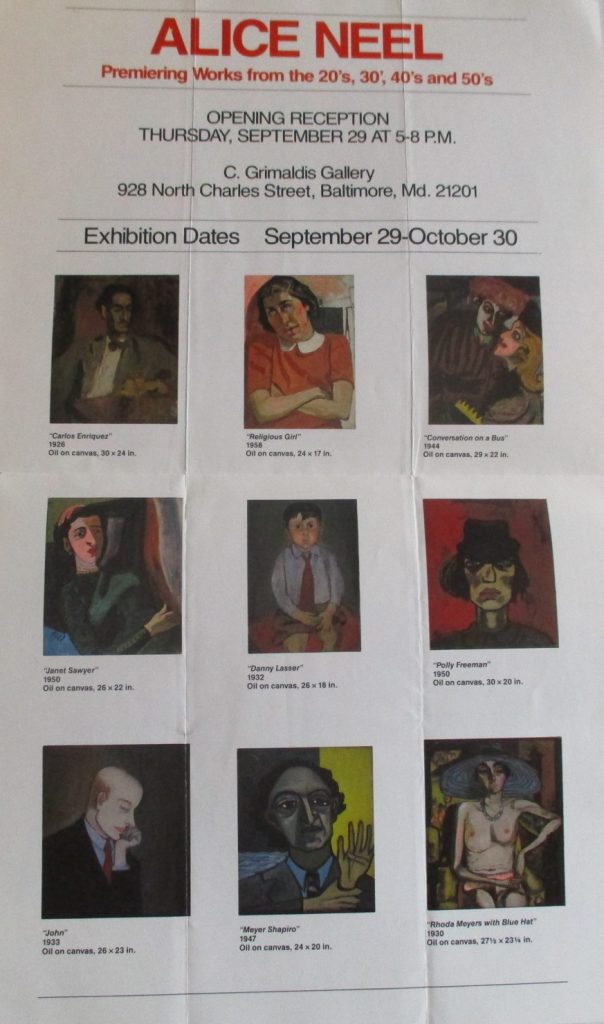

According to the Orlians, the painting left their home only once after they bought it at auction in the early 1970s. Alice Neel personally contacted them, asking whether they would agree to lend it to an important exhibition of her work held at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York in 1983, Alice Neel: Premiering Works from the 20's, 30's, 40's, and 50's. It is a thrill for the Museum to present a relatively unknown Neel painting to a wider public four decades later.

Tony Mattei is currently installed in the Susan and Anton Roland-Rosenberg Collection gallery, Helen J. Haft and J. David Haft Hall, where it is in a fascinating conversation with works by American artists working in the same years—including Morris Louis, Milton Avery, David Park, and Georgia O’Keefe—as well as those by European figurative artists such as Chaim Soutine and Giorgio Morandi. This eclectic mixture of artistic impulses and styles would have pleased Neel, I believe. She resisted all orthodoxies, prevailing styles, art historical precedents, normative renderings of the body—and pursued her own way of seeing and representing people for who they were. Embracing all that was peculiar, honest, and real, she sought to honor human experience, infusing her works with her belief that “You can’t leave humanity out. If you don’t have humanity, you don’t have anything.”

And for me, it is a little piece of New York, a face I can empathize with. The deep lines around the mouth and the eyes seem to suggest the challenges of persevering in New York, and its slightly gritty quality recalls the feeling of the city— long shadows cast by skyscrapers, men rushing around midtown in their suits, the hazy quality of not quite clean air. Here in Tel Aviv, a city of unrelenting sun and year-round sandals, Mattei is a dark beacon in the best sense, an emissary from home, likewise adjusting to unfamiliar yet welcoming surroundings.